Rediscovering the “Ghost Ship” in Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary

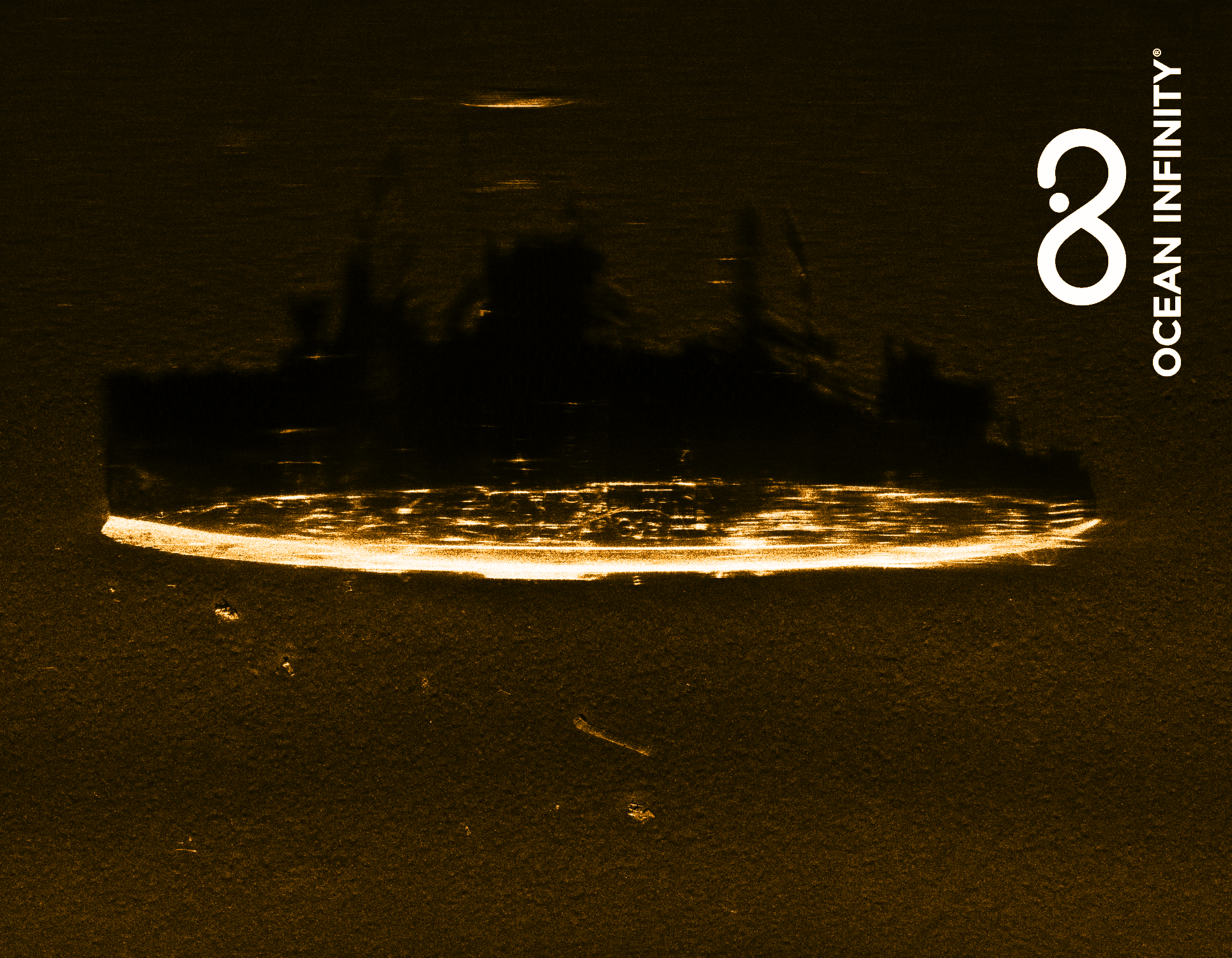

Earlier this year, the wreck of the USS Stewart (DD-224), a destroyer launched in 1920 with a remarkable history during World War II, was located in Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary by Ocean Infinity, a marine robotics company, under a national marine sanctuary permit. This occurred during a collaborative expedition that involved the Air/Sea Heritage Foundation, SEARCH, Inc., NOAA, and the Naval History and Heritage Command.

In light of this exciting news, we caught up with Lilli Ferguson, Resource Protection Specialist with Greater Farallones and Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuaries. In her role, Lilli works to understand and protect maritime and cultural resources within the sanctuaries and is a national marine sanctuary permit coordinator.

We asked her to share more about the incredible story of the USS Stewart (DD-224), where it got its nickname as the “Ghost Ship,” and why maritime heritage is so important.

So, Lilli, what is the story of the USS Stewart?

“The USS Stewart (DD-224), the second ship given the name ‘Stewart’ by the U.S. Navy, served for over forty years, including in WWII, receiving two battle stars, until it came into the hands of the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1942.

Once under Japanese control, they repaired it and modified it to look somewhat like a Japanese ship. They put it into service as Patrol Boat 102, flying the Japanese flag. The U.S. Navy recovered the vessel near the end of the war in 1945, and it was recommissioned as DD-224 (signifying it was a destroyer and including its hull number) as the name Stewart had since been assigned to a different Navy ship, a destroyer escort.

Sailors were very proud and happy the U.S. got the ship back, giving it the nickname, ‘RAMP-224’ or Recovered Allied Military Personnel-224, as if it had been a human prisoner of war. Accounts from the time after it was recovered indicated there was some consideration of celebrating the history of the ship and those who served on it by making it a museum ship, but ultimately, it was decided to sink it at sea as part of a naval training exercise. In an odd coincidence, the third USS Stewart (DE-238) is a featured exhibit at the Galveston Naval Museum in Texas!”

This USS Stewart is also known as the “Ghost Ship.” Where did that nickname come from?

“The ship had been in a floating dry dock in Java for repairs, and an accident with the keel blocks prevented the U.S. Navy from being able to sail it away before it would fall to approaching Japanese forces, so the Navy sank it and the dry dock, thinking that was the end of it and that they would never see it again. Imagine the Navy’s surprise when reports began coming in of what looked like an old Navy destroyer operating behind enemy lines disguised as a Japanese ship. This mystery ship seemed like a ghost, or phantom, from the beyond – the ‘Ghost Ship of the Pacific.’ Turns out, the Japanese were able to raise and repair the former Stewart and put it to use in their navy, with the mystery of what vessel it was solved for certain after the U.S. got it back.

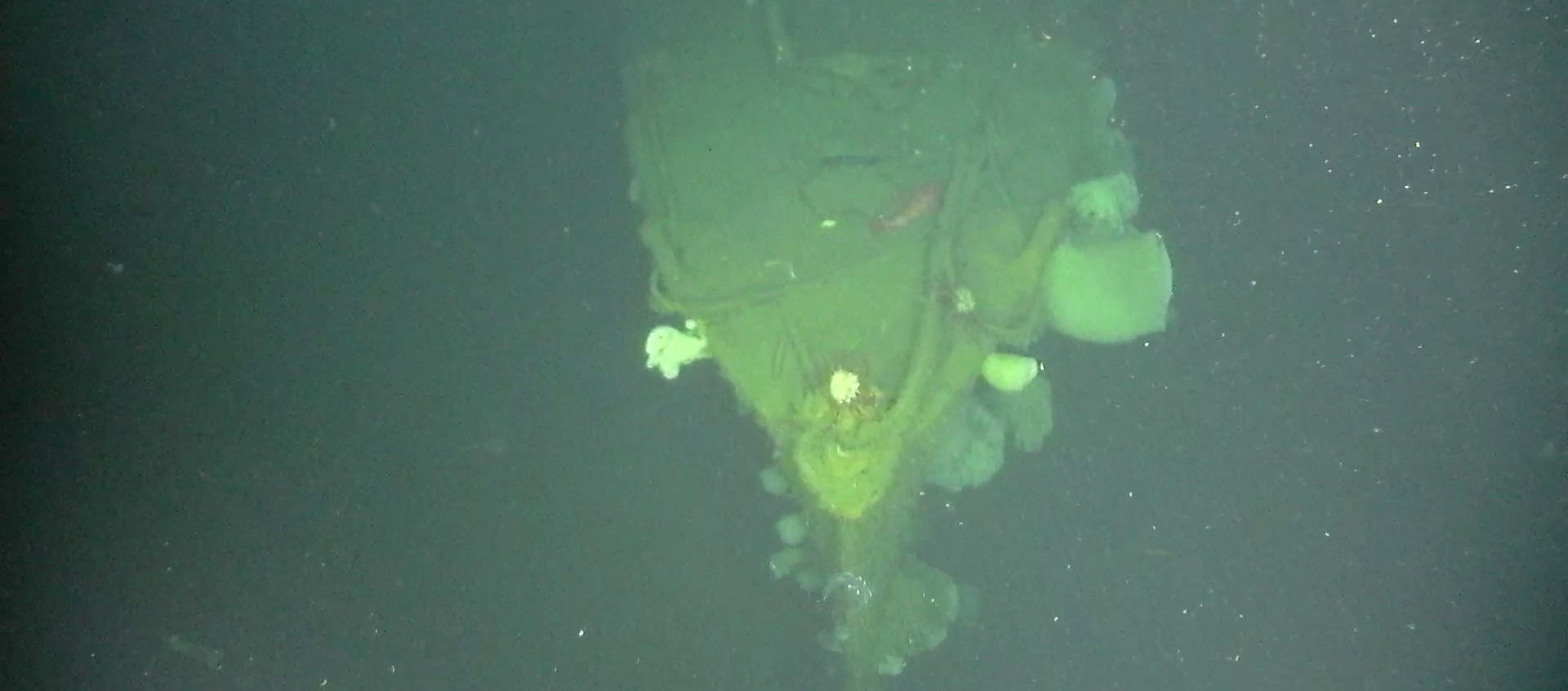

During the recent mission in the sanctuary in which the wreck was located by autonomous underwater vehicles, the initial images appear rather ghostly as well. Shipwrecks and other sunken archaeological items can really get the imagination going.”

What is the significance of this discovery?

“Actually, it really represents a discovery of where upon the Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary seafloor the wreck is resting, as we already knew from historical research it had been sunk, as mentioned, during a naval training exercise within what is now the sanctuary.

Locating the wreck is significant because it provides an excellent opportunity to share the interesting history of the ship with the public. Also, now that we have more information about this important historical and archaeological resource, we can better assess the wreck’s physical condition and manage for its protection into the future, working with partners, including the U.S. Navy. The Navy has management authorities under the Sunken Military Craft Act.

Finally, mapping data and imagery obtained during this mission will also advance our knowledge of the marine habitat and biological communities in the sanctuary.”

What do these types of discoveries teach us about our maritime history?

“That’s a complex question. I think the short answer is, it reminds us of what happened in the past, makes us think about how times have changed, how the past shapes our country today, and how important the ocean, and particularly national marine sanctuaries, are to us.”

Do these types of explorations happen often within Greater Farallones and Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuaries?

“There was a unique set of circumstances for this event in Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary that came together very quickly, and the collaborative public/private research effort (involving NOAA, SEARCH, the Air/Sea Heritage Foundation, Ocean Infinity and the Naval History and Heritage Command) led to an amazing outcome for the sanctuary.”

Are there other shipwrecks within Greater Farallones and Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuaries?

“Yes, there are at least dozens of historic shipwrecks in the overall area we manage (Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary, Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, and the northern portion of Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary) that we know are there and historical documents indicate there could be more, perhaps in the hundreds.

However, shipwrecks are not the only kind of maritime heritage resources within national marine sanctuaries. There are historic port sites within Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, for example. Archaeological and historical resources are tangible evidence of past human activities.”

Historic dog hole port along the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary coastline.

Can you talk about what maritime heritage means and why it is important to preserve?

“It is important to protect tangible heritage resources and tell stories about them because they are unique non-renewable resources and cannot be replaced. NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries explains on its maritime heritage web pages, ‘Maritime heritage is a broad legacy that includes not only physical resources, such as historic shipwrecks and prehistoric archaeological sites, but also archival documents, oral histories, and traditional seafaring and ecological knowledge of indigenous cultures.’

National marine sanctuaries are places that protect prehistoric and historic sites, shipwrecks, cultural resources, and more. They are places for people to explore, discover, and appreciate our country’s cultural connections to the ocean.”

Finally, do you have a favorite shipwreck in the sanctuaries?

“I am not sure I have any one favorite sanctuary maritime heritage resource, but I know the most about the former Stewart (DD-224) and am very happy it was located, for all the reasons mentioned earlier about its significance. In particular, I am happy that archaeologists and marine scientists will now be able to study the wreck and use information about it to inform sanctuary management.”